Africa’s digital sovereignty just suffered a quiet blow.

Earlier this month, South Africa’s TENET — the non-profit serving universities and research institutions — announced it will shut down its long-standing mirror service (mirror.ac.za). For most, the loss may look invisible. But behind the silence lies a bigger question: Will Africa shape its own digital future, or depend on infrastructure it does not control?

For years, TENET hosted local copies of Linux distributions, CRAN (for the R programming language), and other open-source repositories. The reasons for closure are practical: ageing hardware, falling demand, and cheaper global bandwidth. On paper, few will notice the change. In reality, much more is at stake.

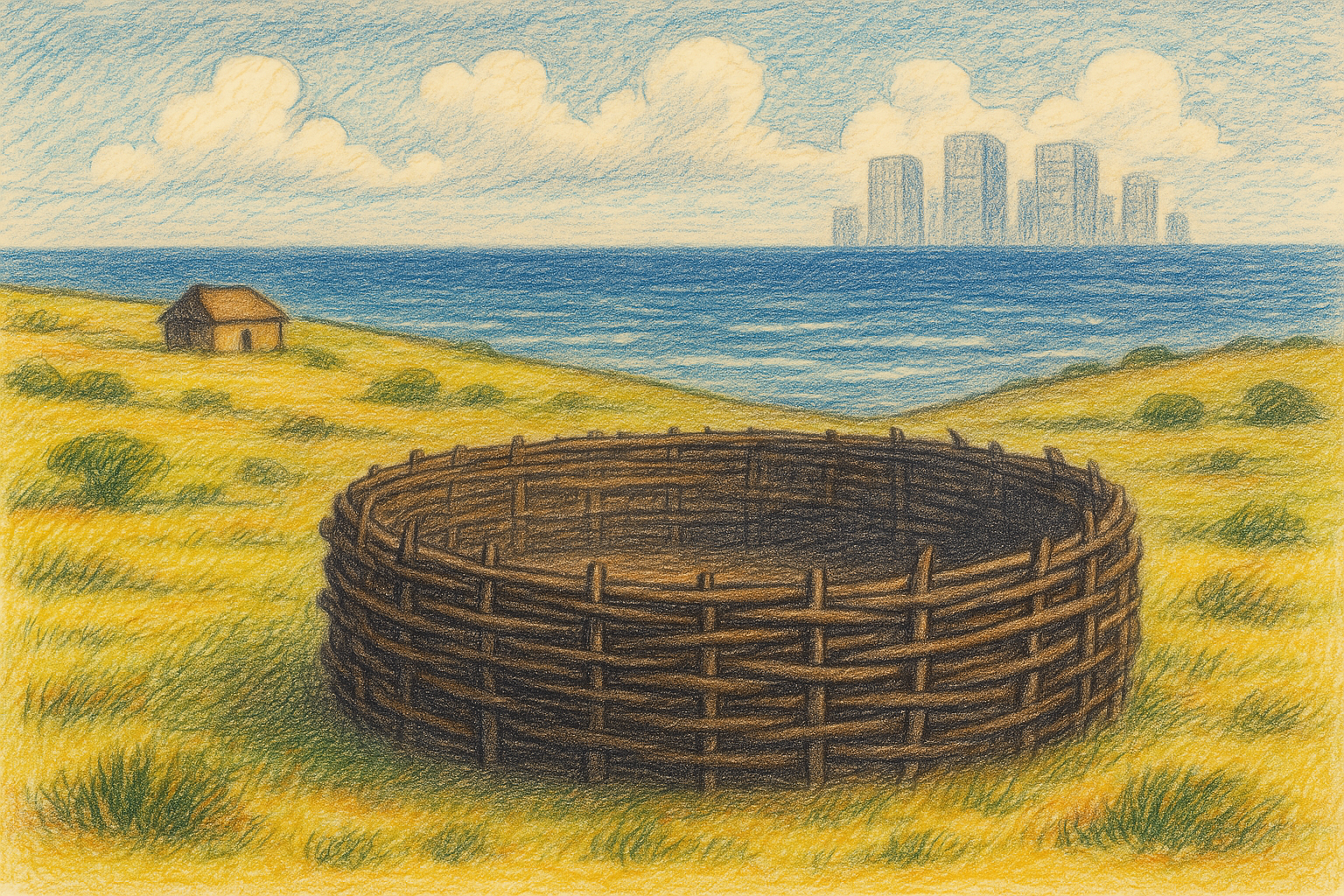

Mirrors are more than speed and convenience — they are trust anchors. They prove our code is genuine. They keep Africa working when undersea cables snap, turning fragility into strength. And they embody a digital spirit of Ubuntu: we build together, and shared infrastructure keeps knowledge open to all.

In March 2024, four major undersea cables — WACS, ACE, SAT-3, and MainOne — snapped, disrupting connectivity across 13 African countries. For days, whole regions were throttled. The lesson is clear: if every byte comes from overseas, a single cut can silence half a continent. Bloomberg

Across Africa, technologists such as Ish Sookun — the only African serving on the openSUSE board and a long-time advocate for Linux mirrors — have long argued for this infrastructure.

Without local mirrors, Africa risks outsourcing its digital commons. Without local mirrors, developers must fetch code from Europe, Asia, or the US. This is more than a technical nuisance. It entrenches dependency, undermines sovereignty, and sidelines Africa from the global conversation on open source.

This isn’t only Africa’s fight.

In 2021, ASREN, WACREN, and UbuntuNet Alliance signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Latin America’s LA Referencia and RedCLARA, committing to “build capacity and infrastructure in our regions rather than rely on centralised infrastructure hosted elsewhere.” AfricaConnect3

It was a clear statement: sovereignty is regional, and resilience comes from hosting at home, not outsourcing abroad. It’s proof that open science infrastructure - including local mirrors - is not just local resistance, but part of a growing global movement for digital equity.

The timing is symbolic. The Johannesburg City Library has just reopened after five years of repairs, a reminder of how access to knowledge strengthens communities. Imagine suggesting that because Kindle and Google Books exist, Johannesburg no longer needs a library. We would reject that argument immediately. Yet this is precisely the logic being used to dismantle our digital commons.

Yes, bandwidth is cheaper, cables are faster, and global distribution is more efficient. But

Efficiency is not sovereignty.

If Africa is serious about shaping its digital future, it cannot depend entirely on servers in the US, Europe, or China. It needs its own mirrors, repositories, and infrastructure — rooted here, for our communities.

Some argue that contribution – writing code, starting projects, and growing communities – matters more than infrastructure. And they are right: without African commits, open source here remains consumption, not creation.

CDNs serve content fast and cheap. But if every byte comes from the US, Europe, or China, Africa is reduced to a client — not a creator.

Mirrors aren’t a sideshow. They’re the foundation.

They cut barriers, train local skills, and prove Africa isn’t only downloading - it’s hosting.

Contribution is more than code. In the spirit of Ubuntu, it’s also resilience. It’s shared provision of the commons.

Trust is human.

A mirror is only as strong as the people behind it. Who runs it, and under what rules, matters as much as bandwidth. Confidence comes from transparent stewardship — by universities, NRENs, and communities.

And mirrors mean reciprocity.

They show Africa is not just consuming open source but investing in it. That’s how servers become symbols. That’s how technical infrastructure turns into social infrastructure — the trust Africa needs to stand as a peer in the global commons.

The real question is not whether mirrors are technically necessary. It is whether Africa intends to stand at the heart of open-source innovation — or remain at its margins.

Building mirrors is not nostalgia. It is sovereignty. It is resilience. It is reciprocity.

The world will not wait. The question is simple: will Africa?